By Mallory Durkin

B.A. ’23, International Affairs

Through Philip Troutman’s “Race, Gender and GW History” course, I conducted archival research to examine the treatment and perception of gay students on GW’s campus during and following the height of the 1980s AIDS crisis. To begin my research, I obtained physical and scanned copies of The Hatchet and the Cherry Tree Yearbook from the 1980s to today, using the Special Collections Research Center in Gelman Library. My search revealed numerous documented cases of outward homophobia extending well into the 1990s. To delve deeper into these incidents, I examined publications in the weeks surrounding each incident to gauge how both the university and student populations responded.

Through reading testimonials written by openly gay students coupled with records of Gay Awareness Week materials and speakers coming to dispel myths about AIDS, it became clear that GW’s gay community has faced many tribulations. Despite it all, GW’s LGBTQ+ students have remained resilient, present, and represented for over forty years.

The most blatant example of homophobia I discovered occurred in October 1989 when GW sophomore and public relations director of the College Republicans – Ross Allyn Matlack – published an article in the College Republicans’ publication, the CR Observer, titled “Ethics and Democrats are like Drinking and Driving.” Articles published in The Hatchet in response to Matlack provide examples of the hostile language he used:

“Homosexuals are idiots. If these deviates chose to keep their sins to themselves, perhaps they could be tolerated. But as it is, they are seeking rights that are reserved for normal citizens, such as marriage and adoption. These people are unfit to live, let alone raise children.”

– Ross Allyn Matlack

Critics claimed Matlack aimed to intentionally provoke gay students and allies and directly following the article’s publication outrage erupted across campus. Authors in The Hatchet compared Matlack to Hitler as he appeared to condemn innocent people to death because of aspects of their identity that were entirely out of their control. The editor-in-chief of the CR Observer at the time, Jennifer Wilson, stated that she allowed the piece to be published because although she personally did not agree with statements made in the article, she believed Matlack had the right to publish it as it would not directly harm any students.

After the Matlack Incident of 1989, College Republican Jon Cramer published an article titled “Being a Gay Republican is not a Contradiction in Terms” in The Hatchet explaining how as a gay man, a Roman Catholic, and a Republican he was “disgusted” by Matlack’s article and wanted to clarify that his views did not represent all Republicans. Cramer wrote:

“I am sorry to burst your GOP-loving bubble, but even Republicans are included.”

– Jon Cramer

Cramer explained that there is no single version of who a gay person is. In his article, Cramer referenced the Capital Area Republican Club, an organization comprised of gay Republicans, as evidence to support his point that not all Republicans subscribe to Matlack’s views.

One of the first examples of homophobia I unearthed in The Hatchet archives was a write-in submission published in The Hatchet in 1985 authored by Jordan Lorence, an attorney from Concerned Women for America. In the article, titled “Homosexuality a moral issue” Lorence stated that “the basic problem with the gay rights movement: a morally suspect group craves legitimacy so much, it will attempt to coerce acceptance from an unwilling majority,” and claimed that “homosexuals have hijacked terminology from the civil rights movement” to promote their own agenda. The fact that GW published this article in the student newspaper also reveals that, although GW was progressive enough at the time to have LGBTQ+ student groups on campus, hatred and discrimination remained rampant.

In 1990, multiple articles appeared in The Hatchet revealing that gay men were meeting in the student center’s bathrooms, perhaps because restrooms were among the only places LGBTQ+ students could gather privately and safely on campus. GW’s administration, however, did not address the core issue, and instead, brought in security, including Captain Anthony Rocco Grande, a police officer who was attempting to bar “suspicious individuals” from the center’s bathrooms. He suggested that “students can become the eyes and ears of our department,” as they became hyper-alert for gay students and their activities. These reports and statements contributed to a negative perception of gay students across campus.

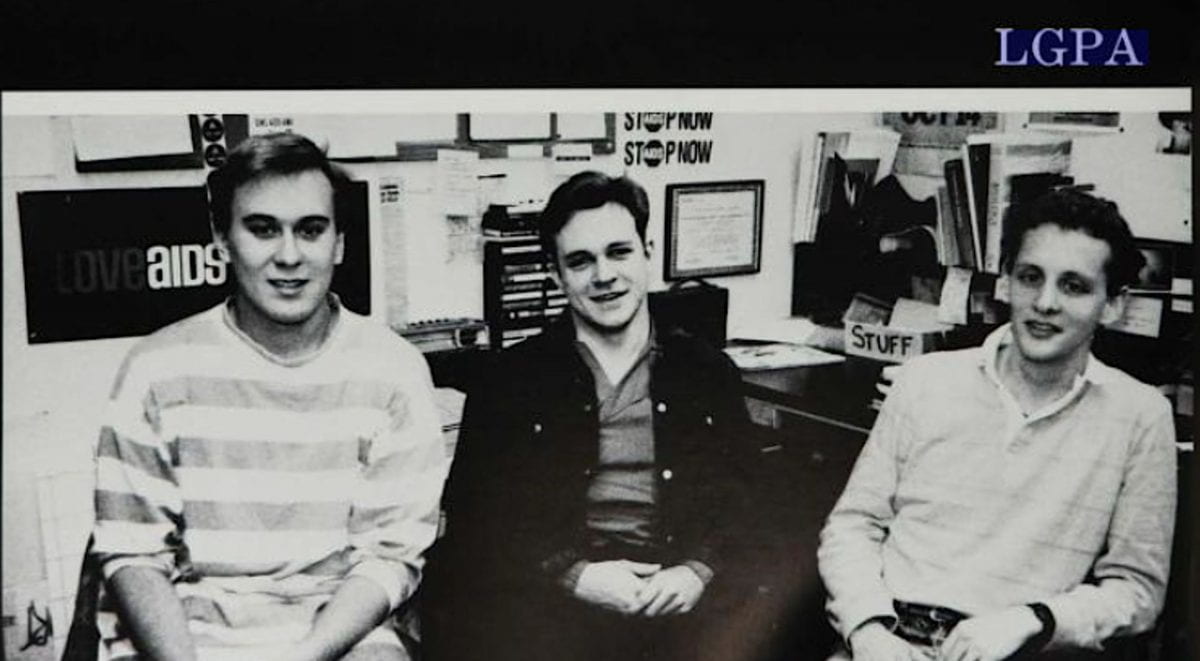

A 1992 Hatchet article titled “Homosexuals gain social acceptance but they still face strong opposition” clearly described the climate for gay students at GW in the early 1990s as LGBTQ+ students became increasingly visible across campus. Gregory King, a 1976 GW graduate, observed that while “society has become more open and accepting, those who oppose gays have become more angry and violent.” He explained how GW existed as a medium between the two extremes and that people are “tolerant, but not necessarily accepting.” He noted that “GW is not blatantly homophobic but…the atmosphere on campus encourages gays to hide in the closet rather than come out.” This sentiment is perhaps best exemplified in the photograph (below) representing members of the Lesbian and Gay People’s Association in the Cherry Tree Yearbook from 1989. The photograph leaves many unanswered questions, given that the group’s enrollment was larger than three people. It is likely that other members were not comfortable enough to be photographed because of pervasive homophobia across campus.

In the same 1992 article, GW junior Kathy Wittes exemplifies the type of homophobia that still permeated campus when she stated that “[gay] people choose to be this way… homosexual practices are self-destructive.” As these remarks demonstrate, the accepting campus environment that GW fosters today was clearly a far cry away as recently as the 1990s.

A Shift Toward Acceptance

Despite homophobic remarks made by GW students, advertisements in The Hatchet reveal inclusivity-minded programs sought to dispel harmful stereotypes beginning in the late 1980s. For example, the school sponsored AIDS and Gay Awareness Weeks and “Safe Sex Fest” events claimed to “succeed in (their) goal of educating students about AIDS and desensitizing students to condoms.” Although less than fifty people were reported to have attended Safe Sex Fest, the public event demonstrated that the school was taking active, preventive measures at de-stigmatizing and discussing AIDS, which disproportionately impacted LGBTQ+ communities.

Perhaps the largest gesture of solidarity made by GW in the 1990s occurred when GW’s Program Board brought the AIDS Memorial Quilt to campus in March of 1992. A creation of the Names Project, the Memorial Quilt was a national response to the AIDS crisis honoring the names of those who died from the HIV virus. Created by volunteer artists from across the country, each three-by-six-foot wide panel (the size of a grave) contained a victim’s name or message relating to the crisis. With over 94,000 names, this incredibly moving artwork became an iconic memorial. Upon its arrival at GW, over 2,000 GW students came to view the quilt. GW’s yearbook also noted increasing recognition of the humanity of the crisis when they reported that in April of 1994, 500,000 LGBTQ+ individuals came together in Washington D.C. to honor those lost to AIDS. These gestures of solidarity demonstrate how conversations around AIDS and the LGBTQ+ community had shifted from disgust and anger to increased feelings of loss and mourning.

GW has had a long, complicated history with LGBTQ+ community members and it is shocking to witness how the student body’s views have shifted so drastically just in the past twenty years. It will surprise many how such inflammatory language was tolerated and published as recently as the late 1990s. Reflecting on GW’s past, however, is important if we are to better understand campus culture today. This knowledge betters our modern understanding of the evolution of homophobia, gay pride, the LGBTQ+ rights movement, and reflects cultural shifts occurring not only on campus, but across the nation. In the past few years, cases of homophobia have still been reported across GW’s campus, and although today most of GW’s population seems to have shifted towards accepting and celebrating community members who identify as LGBTQ+, it is crucial to remember GW’s fraught history in order to both honor those who overcame tribulations before us, and to strive for more equity in the future.

This post was written during GW’s bicentennial year in conjunction with the museum’s Two Centuries of Student Stories exhibition, which looked back on 200 years of campus life through artifacts from the University Archives.