By Lee Anne Spear

M.A. ’23, Museum Studies

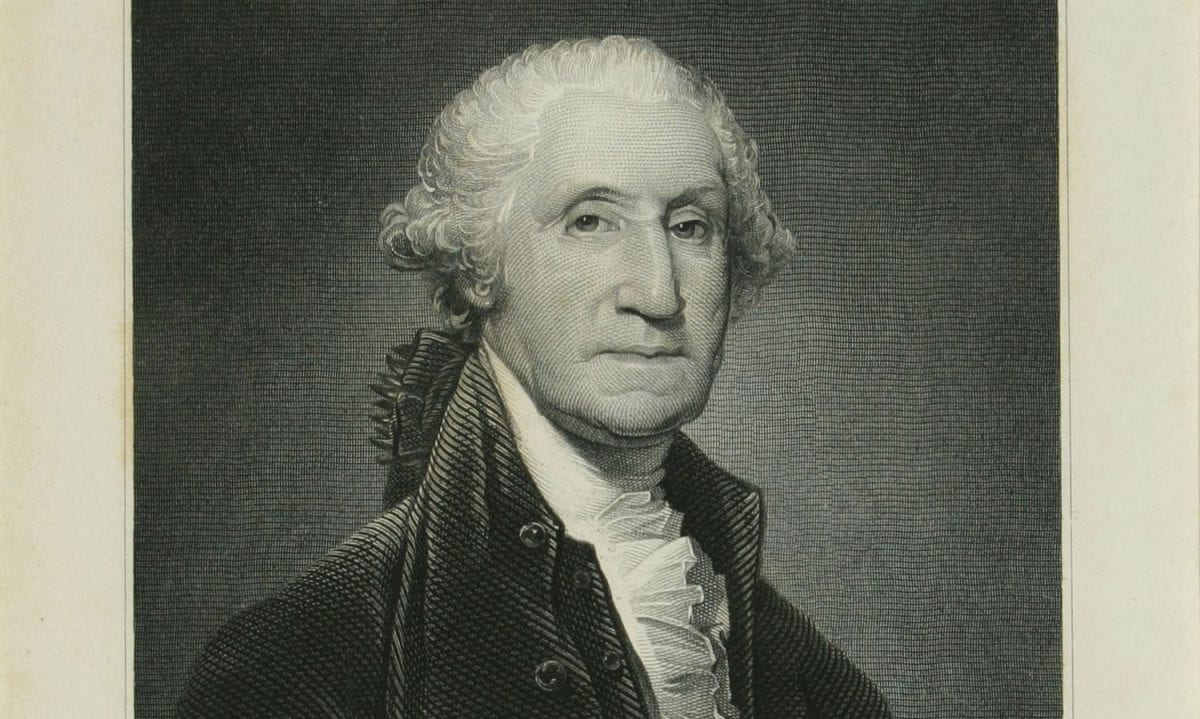

A special post in honor of President George Washington’s birthday.

It is fitting that we celebrate President’s Day today, on the birthday of the first president of our nation. George Washington’s legacy stands alone, unique from even his fellow founders. Washington was a patriot, a strong military leader and a president who symbolized legitimacy for a newly formed nation. He led a small army to victory against a massive empire, and shaped the customs and prestige of the American presidency. Overtime through these lenses Washington has become a “marble Adonis,” a standard impossible to meet for any president to follow.

It is impossible not to acknowledge the immense impact Washington had on the new United States. When he stepped down from the presidency there was no clear successor to fill the void. He set the standard that the government is bigger than one person, and was one of the first to identify as an American first and by his state identity second. At the end of the Civil War he was spoken of as a shared history for the north and south, a unifying symbol of patriotism. What often gets lost in these conversation is the importance of the nuance of a whole person. Shortly after Washington’s death it became common for anything but absolute reverence to be criticized and ignored. His role as an enslaver highlights the dark side of the independence movement. Washington was not passive in his role as an enslaver. He profited from the labor of enslaved people, he refused to speak out against slavery publicly and he actively pursued enslaved people who escaped. To circumvent Pennsylvania’s abolition laws, Washington would rotate enslaved people between his Virginia plantation and the Philadelphia President’s House. While in Philadelphia in 1796, Ona Judge escaped from the home. The Washingtons hunted her until George Washington’s death in 1799.

Washington did emancipate the enslaved people of Mount Vernon in his will, though they would not receive their freedom until after the death of Martha Washington. Some argue his choice to emancipate in his will was a sign Washington knew enslavement was morally wrong and regretted his participation in the practice, that the only reason he did not make a statement in life was for fear of southern secession. Others argue an apology in death is not an erasure of guilt and that his main motivation for emancipation was fear over how he would be remembered in posterity. In an avoidance of this discussion of complexity, most authors and artists’ depictions of Washington seem to be in agreement to “declare him too marble to be real,” an unapproachable hero, a “god like apotheosis.” Such a singular view means we never really get to know Washington as a whole, flawed, very real man.

Washington’s position as an untouchable American hero is also influenced by artistic depictions of him. Sculptors carve his figure from marble, modeling his pose and dress after Greek and Roman gods. Washington appears muscular, young, and wearing a toga rather than his military uniform. Such an interpretation transforms the president into a mythological demigod of liberty rather than a farmer turned politician.

Monuments to Washington follow a similar pattern. Often made of stone or bronze, each monument seeks to uphold an otherworldly elegance and strength. The most iconic being the Washington Monument in D.C., a 555-foot marble obelisk. Across the Potomac is the Freemasons’ monument to Washington, a towering structure modeled after the lighthouse in Alexandria, Egypt, and the Parthenon. Other monuments to Washington are done in the equestrian style. Generally these monuments have a heavy stone pedestal with a bronze sculpture of Washington on horseback placed on top. While less a god-like image, they quite literally place the general and president on an untouchable pedestal. While Washington is not the only American figure to be memorialized in this fashion, it is an important part of how we understand his legacy.

Looking at how Washington is portrayed in paintings and portraits gives yet another example of how our memory of him has been shaped. Nearly every American has seen an image of the “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting. One of the most iconic depicting the revolutionary period, it is not only considered a beautiful piece of art but an important piece of history. Washington stands above the soldiers rowing the boat. His uniform clean, his stance steady and strong. Behind him the American flag blows in the cold wind. The only well lit portion of the sky sits behind Washington, illuminating his figure and the flag. In this painting and many others, Washington is made into a symbol of military prowess and American liberty.

As we near 250 years of American independence, it is important to reflect on how we study and understand our heroes. Beneath the layers of stone and marble laid over centuries is a flawed, yet still incredible man. He led 13 colonies to victory over an empire, then led a group of somewhat inexperienced statesmen to shape a system of government we still live under today. Yet he was also an enslaver who did not support Indigenous rights or claims to the land. This dichotomy can exist and must exist in order for us to understand where we came from and where we need to go next. We can still celebrate all Washington did for our country while recognizing he was no more than human and capable of making mistakes. Washington knew we would look back and study him centuries later, but he also knew he was human and would leave behind a complex legacy. It’s a complexity that symbolizes the history of a nation founded as an experiment in freedom and democracy. Perhaps the Broadway musical 1776 said it best, “What will posterity think we were, demigods? We’re men, no more, no less, trying to get a nation started against greater odds than a more generous god would have allowed.”