By Ritah Magera, B.S. ‘27, Criminal Justice

Leila Shahidi, B.A. ‘26, Organizational Sciences

Isabela Gonzalez , B.S. ‘27, Biology

Washington, D.C., is renowned for its iconic monuments, museums and political history. However, nestled amid the city’s magnificence is a lesser-known, yet equally significant, aspect of its history — the hidden or “blind” alleyways. These narrow passages, often overshadowed by D.C.’s main tourist attractions, hold a wealth of stories and provide a glimpse into past inhabitants’ lives.

On February 5, 2024, Kim Prothro Williams discussed her new book, The Hidden Alleyways of Washington, DC (Georgetown University Press, 2023), as part of the D.C. Mondays series at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum. Williams is an architectural historian, focusing on the District’s local history, neighborhoods and urban planning developments. She currently serves as the national register coordinator at the D.C. Historic Preservation Office.

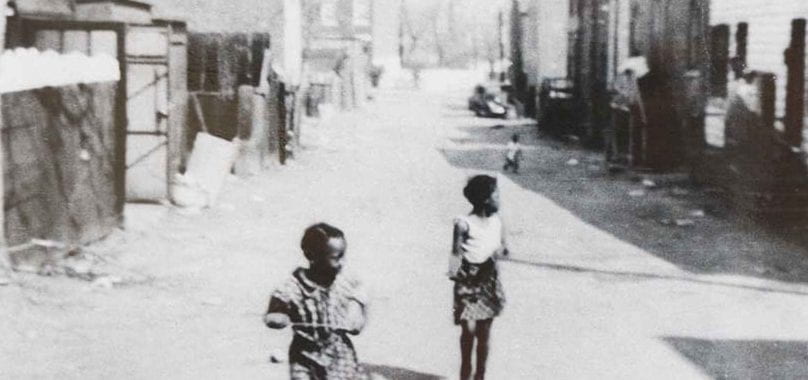

Washington, D.C.’s alleys were initially built within larger lots, forming insular communities separate from the city’s main thoroughfares. Before the Civil War, 49 alleys supported about 300 households. White immigrant workers and their families inhabited these alleyways, often living in houses built behind their employers’ lots. During the Civil War, an influx of African Americans escaping slavery sought refuge in the alleys.

Living conditions could be deadly, with most homes lacking plumbing, heat, insulation and sewage systems. Government officials and certain White progressive reformers blamed the alleyways for contributing to crime and suffering, and some considered them detrimental to civilization itself. Early humanitarians supported building regulations, that banned wood construction and established minimum house widths, as well as requirements for toilets or outhouses. Although conditions improved, health issues persisted.

Despite the poverty, alleyways were home to tight-knit communities, with areas like town commons serving as community centers, schools and churches. The alleyways were also a hub for artists such as John J. Early and Paul Bartlett, contributing to D.C.’s cultural richness. The Krazy Kat Klub, located off of Massachusetts Avenue, was a Bohemian cafe, speakeasy and nightclub, exemplifying the alleys’ vibrant artistic communities.

In 1936, a congressional mandate replaced many alley dwellings with new housing, displacing African American residents and making room for White professionals. Alleys were renamed to shed negative connotations (e.g., Bells Court became Pomander Walk). Throughout these changes, the history of the alleyways was not widely interpreted or understood. Some alleyways, like Cady’s Alley in Georgetown, have since been repurposed into commercial housing and designer stores with little effort to highlight their historical significance.

The history of Washington’s alleyways reflects broader social and economic changes, from the settlement patterns of immigrants and people escaping slavery to the impact of housing reform and urban development. While alleys were once emblematic of poverty, efforts to renovate and reinterpret these spaces continue, albeit with mixed success in preserving their rich historical and cultural narratives. Williams’s book covers these topics and more, offering a deeper look at the alleys’ history. You can watch a video of this D.C. Monday program below and browse upcoming talks.

This post was written by students in Professor Jessica McCaughey’s COMM 3190 class at the George Washington University.

About the Authors

Ritah Magera is an undergraduate student at the George Washington University, majoring in criminal justice with a minor in psychology. Originally from Uganda, Ritah aspires to become a lawyer and currently works as a student project assistant at the Nashman Center. In her free time, she immerses herself in true crime podcasts, deepening her understanding of the U.S. legal system.

Leila Shahidi is an undergraduate at GW majoring in organizational sciences with a minor in communications. She lives in Westchester, New York, and is interested in pursuing a career in the fashion industry. She’s a member of GW’s Fashion Business Association.

Isabela Gonzalez is an undergraduate at the George Washington University, majoring in biology on the pre-health track. A Miami native and bilingual in Spanish and English, she brings a strong background in community service and leadership from her time at Gulliver Preparatory. Eager to specialize in Pediatrics, she strives to enrich her academic journey with clinical experiences and internships in D.C.

Header image: Poplar Alley, Georgetown, c. 1920. Image courtesy of the Peabody Room, Georgetown Neighborhood Library.