By Silvia Cassidy

B.A. ’25, Political Science and Religion

I grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, a small city situated at the crossroads of the Midwestern and Southern United States. It is a parochial town where many neighborhoods are named after the Catholic churches they surround. Having grown up in such an insular place, international politics seemed incredibly distant.

When I first arrived at the George Washington University in 2021, I felt the ripples of international conflicts in everyday life. I was studying alongside students living through conflicts I’d previously seen only as headlines.

One regular Friday in November, I remember walking down E Street as I entered the Elliott School for an economics discussion. Suddenly dozens of students waving Palestinian flags and signs began marching down the sidewalk. Their commitment and deference to their cause struck me. For the first time I saw that the Israeli-Palestinian debate was not so distant and deeply personal to fellow classmates.

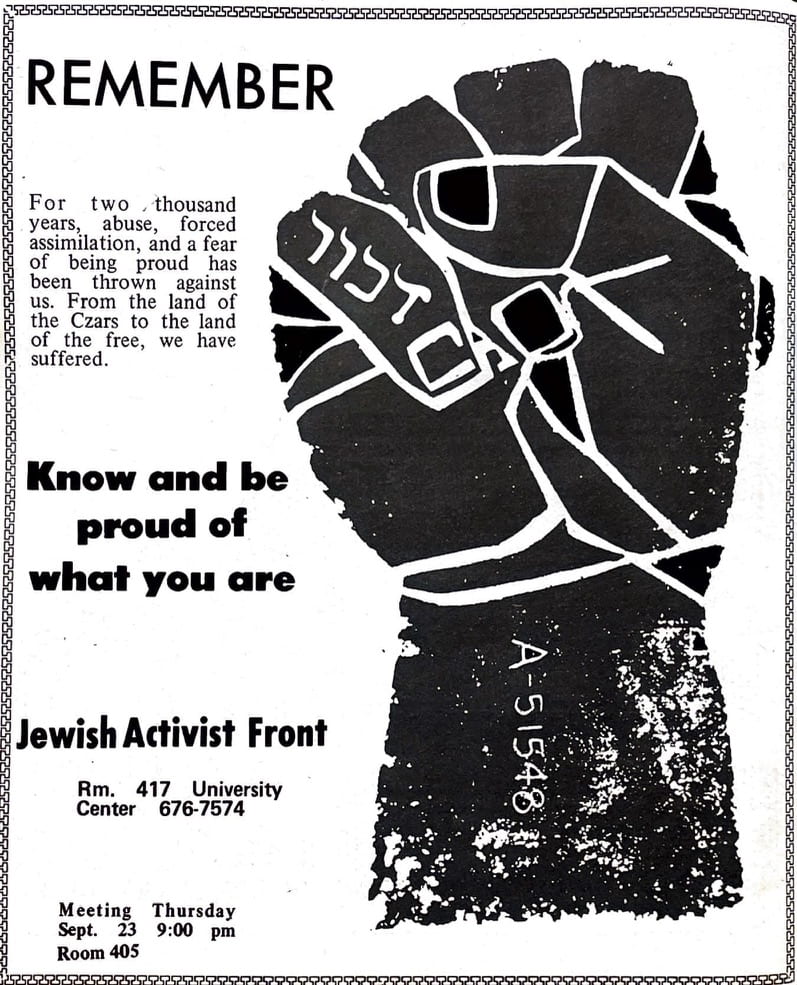

Hoping to learn more about the history of the Isreali-Palestinian debate across campus, I began researching the Jewish Activist Front (JAF), a political group with vague ties to the GW Hillel, that held a firm pro-Israeli stance in the second half of the 1970s. Through my archival research, I realized that the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict is not a new source of tension at GW.

In 1970, when the JAF first formed, they identified as an “action and propaganda group” supporting two main causes: the Soviet Jewry Movement and responding to anti-Zionist rhetoric on campus. The JAF also sought to elevate Jewish identity by advocating for students to celebrate Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur without academic penalty.

Although JAF’s members developed a strong sense of unity, they did not build cross-cultural connections with other national or religion-based organizations — especially groups that took pro-Palestinian stances. JAF members quickly rejected dissenting opinions from other student groups.

JAF became increasingly insular beginning in 1973. Late one Thursday, a firecracker shattered the People’s Union office window and a threatening note was left at the Youth Socialist Alliance (YSA) and Organization of Arab Students (OAS) office. All of the aforementioned groups critiqued the pro-Israel position. The following Sunday Swastikas were carved into the door of the JAF’s office accompanied by a note that read, “’Beware JEWS!!! Palestine for the Palestinians! We will avenge the 100 Libyans! Death to all Jewish Racist Criminals!'”

Instead of finding unity after the attacks, the JAF alleged that the People’s Union, YSA, and OAS fabricated the assault on their office. Members of those groups denied the charges, contending it obscured the violence and the political issue at hand. They also maintained that their anti-Zionist position did not equate to anti-Semitism, as the JAF had implied.

Shortly after the firecracker incident, the People’s Union held seminars on issues in the Middle East including the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. At the first seminar, a spectator reported that JAF members taunted panelists representing the spectrum of the Israeli-Palestinian debate with sarcastic questions and snickered as a Palestinian described his experiences under the Israeli government. Afterwards, the JAF held their own seminars and removed advertising and literature about the People’s Union lectures.

The JAF’s condescending attitude transgressed over the next couple of years, and other students began responding. In 1975 when WRGW, GW’s student-run radio station, launched a program granting air time to campus organizations, the International Student Society (ISS) was one of many groups given a three-minute time slot, mostly using it for social announcements. But in early October 1975, Damjan Gruev, an ISS member in charge of producing their broadcast, used the platform to criticize the JAF. He declared that JAF members were “‘intolerant, militant people who do not have any respect for anything or anyone else but their own people.’”

Gruev’s charged language marked the beginning of a combative tug-of-war between the ISS and JAF. That November, two University of Maryland students attacked ISS president Mohammed Faurki while he was leaving an event hosted by the United Jewish Appeal. While the JAF condemned the violence, Faurki himself pointed out that “the biased news coverage… and a general air of manufactured tension” cultivated an environment where such hostilities could surface.

Following Greuv’s radio remarks, the JAF engaged in a politicking campaign. While the group disassociated themselves from the Faruki attack, the student body was already exhausted with the JAF’s tit for tat tactics with other campus organizations.

This behavior developed into the late 1970s when JAF experienced the greatest pushback for an act performed by some of its members in the autumn of 1977. During lunchtime, in what is now the University Student Center, four students marched into the cafeteria after blowing a whistle, one wearing an eyepatch and the others dressed in “traditional Arab costumes.” One student waved a toy pistol in one hand and an olive branch in the other. “I’m Arafat, I’m Arafat we want peace in the Middle East!” they exclaimed, indicating they represented former president of the state of Palestine Yasser Arafat. A moment later, a pop echoed across the cafeteria as Arafat “shot” the person with the eyepatch representing Israeli Foreigner Minister Moshe Dayan, while the remaining members of the troupe hoisted a banner reading “Geneva Peace Conference.” Shock met the onlookers, some of whom were unsure if the assassination was real or not.

In response to the incident, a Hatchet editorial commanded the Jewish Activist Front to “Cool it.” They wrote that the JAF’s feud with the ISS two years earlier had brought a “petty, childish circus” to campus. Students also reacted to the incident calling it “insulting” and “insensitive.” One noted, “There are enough formal means of expression on campus, such as the Hatchet and WRGW, so that students should not have to resort to provocative incidents to let their opinions be known.”

After 1981, the JAF was never mentioned in the pages of The Hatchet again. My research in the archives did not indicate any commensurate group took its place. However, the history of the JAF – its identity politics and rigid rejection of other ideas – lives on as an important reminder that an unwillingness to engage in dialogue combined with an unyielding ideology can isolate potential supporters. Would the JAF still exist had they pursued open dialogue with those holding opposing views?

This post was written during GW’s bicentennial year in conjunction with the museum’s exhibition Two Centuries of Student Stories, which looked back on 200 years of campus life through artifacts from the University Archives.