By Lee Anne Spear

M.A. ’23, Museum Studies

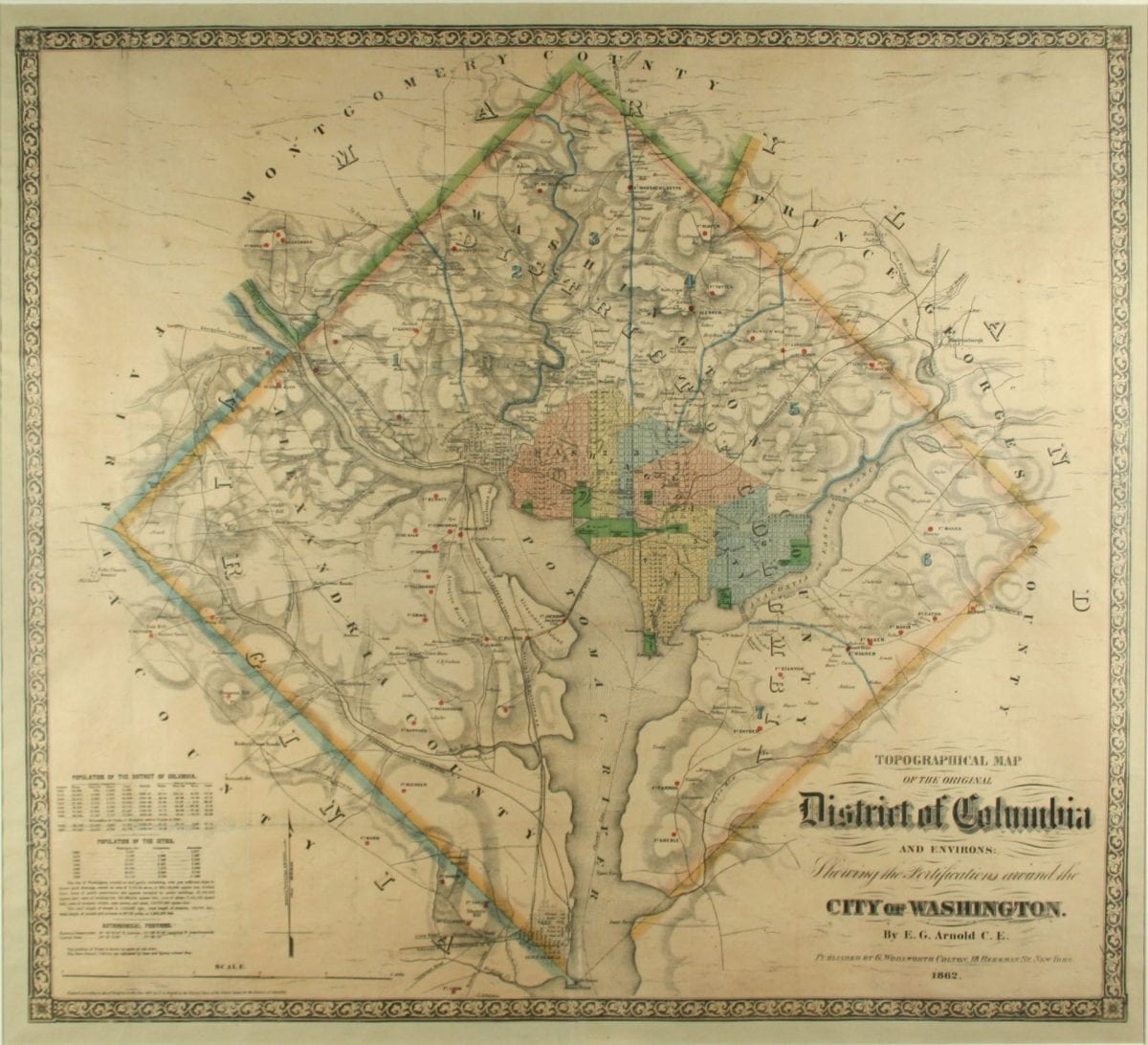

E. G. Arnold’s topographical map published in 1862 is now one of the rarest from the American Civil War period. Arnold’s map depicts the District of Columbia’s original boundaries, including the land ceded back to Virginia in 1847, now know as Alexandria, Virginia. The map outlines school districts and provides historical population data. Most importantly it shows detailed routes in and out of the District by road and railroad, and plots the many forts protecting the city (indicated by red dots).

Arnold’s map depicts D.C. as it was shaped by the Civil War. The city was no longer Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a small federal town, but a bustling city with a constantly growing population. As construction began for new government buildings, military barracks and new homes the city expanded outward into formerly rural areas.

Despite the population boom during the war, getting in and out of D.C. during the war could be a difficult task. By 1862, a total of 48 forts and batteries protected the capital. In addition to those fortifications several checkpoints were set up along roads to monitor who was coming in and who was leaving D.C. Residents and visiting government officials needed signed passes, which included an oath of allegiance, to enter or leave the city through these checkpoints.

After Virginia voted for succession, Union troops decided to occupy Alexandria as further support of fortified defenses. Defense of the capital was a top priority for Union officials, especially after their loss at the second Battle of Bull Run just 30 miles outside of D.C. An invasion or fall of Washington, D.C., could mean the Civil War would end with Confederate victory, permanently dividing the United States. With a Union loss so close to the nation’s capital, many feared an attack was near.

“By latest accounts the enemy is moving on Washington . . . Let us be vigilant, but keep cool.” – President Abraham Lincoln

July 16, 1864

Surprisingly the United States government and military were actually unaware of the creation of the Arnold map until after its publication. Arnold published his map of the District with publisher G. Woolworth Colton and neither man notified the government of the sensitive information that would be included on the map. Previously there were no maps or published information depicting exactly where all 48 forts were located. Releasing this information to the public was a serious risk to the security of the capital city. If the map had made its way into Confederate hands it would have provided a detailed roadmap for an attack on Washington, D.C. In an effort to avert that risk, the Secretary of War ordered the destruction of all copies of the map.

“…two days after the first copy had been put on sale, the rumor of its existence reached the ears of the War Department, and the officers of the law swooped down on the bookstores and gobbled every copy in stock….

Washington Post, Nov. 16, 1892

The order to destroy or turn in the maps mostly succeeded. Only a few copies survived at the time, and even fewer still exist today. As a result, the 1862 E.G. Arnold map is one of the most sought after by private collectors, museums and Civil War enthusiasts. It tells the story of a city flourishing in the midst of war and tells us just how close the violence of the Civil War came to our nation’s capital and the seat of our democracy.