By Lee Anne Spear

M.A. ’23, Museum Studies

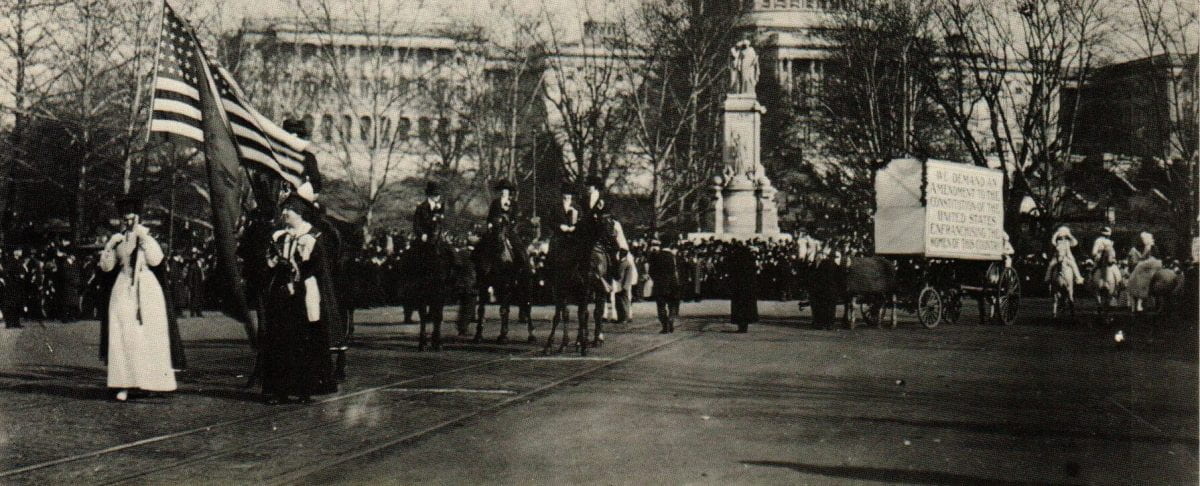

Protesting at the White House is standard practice for American activists, regardless of their cause or the political affiliation of the sitting president. For anyone who has visited the White House this probably comes as no surprise, but many do not know how this tradition started. The first protest held at the White House was in support of women’s suffrage. On January 10, 1917, twelve women braved the cold to picket at the White House demanding that the government recognize their right to vote as citizens of the United States. The picket was organized by international activist Alice Paul, who was also instrumental in the first women’s march on D.C. four years earlier. Paul had spent several years in Great Britain working alongside English suffragists and was inspired to bring their tactics across the ocean to help American women in their fight.

These women became known as the twelve Silent Sentinels. Their picket was peaceful, an attempt to shame President Woodrow Wilson for his opposition to women’s rights. The women knew the picket would have to be asustained effort in order to make any difference and knew they would likely face the same harassment and violence the marchers faced in 1913. Not only did the Sentinels face opposition from those who condemned women’s suffrage, but many also claimed these wartime protests were unpatriotic and accused the women of being anarchists and disloyal. Police arrested the picketers throughout the year. The women were charged a fine and most refused to pay in protest. Many were given six-month sentences in the District’s Occoquan Work House. Despite the challenges, women consistently volunteered to participate in the White House picket.

While in the Occoquan Work House the women were abused and subjected to unconstitutional punishment. Alice Paul recalled being forced against her will to undergo physical and mental examinations by five different doctors. When the women coordinated a hunger strike in protest of their imprisonment and treatment they were force-fed through a tube leading to bleeding, broken teeth and choking. When released suffragettes spoke out about their mistreatment, guards would punish the still-imprisoned women. Many recalled being “brutally handled” and injured. News of this abuse convinced President Wilson to change his views on women’s suffrage. He pardoned the picketers and announced his support of their movement in New York that fall and later advocated for the cause in his annual speech to Congress that December.

The least tribute we can pay them is to make them the equals of men in political rights as they have proved themselves their equals in every field of practical work they have entered, whether for themselves or for their country.

President Woodrow Wilson

While we remember these picketers and the women’s suffrage movement as inevitable, these women were considered radical and their boldness scandalous. Their choice to protest directly to the president evolved over time into what we see almost daily on the White House grounds. Over time the White House has seen protests in support of civil rights and LGBTQ+ rights, anti-war protests during the Vietnam War, and even protests related to international issues such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Each of these groups followed the suffragettes’ example, and each faced the same criticism and fears of arrest and harassment for their radical views. Even 100 years later, a protest at the White House remains one of the most visible ways for Americans to use their First Amendment right to free speech and dissent.