By Lee Anne Spear

M.A. ’23, Museum Studies

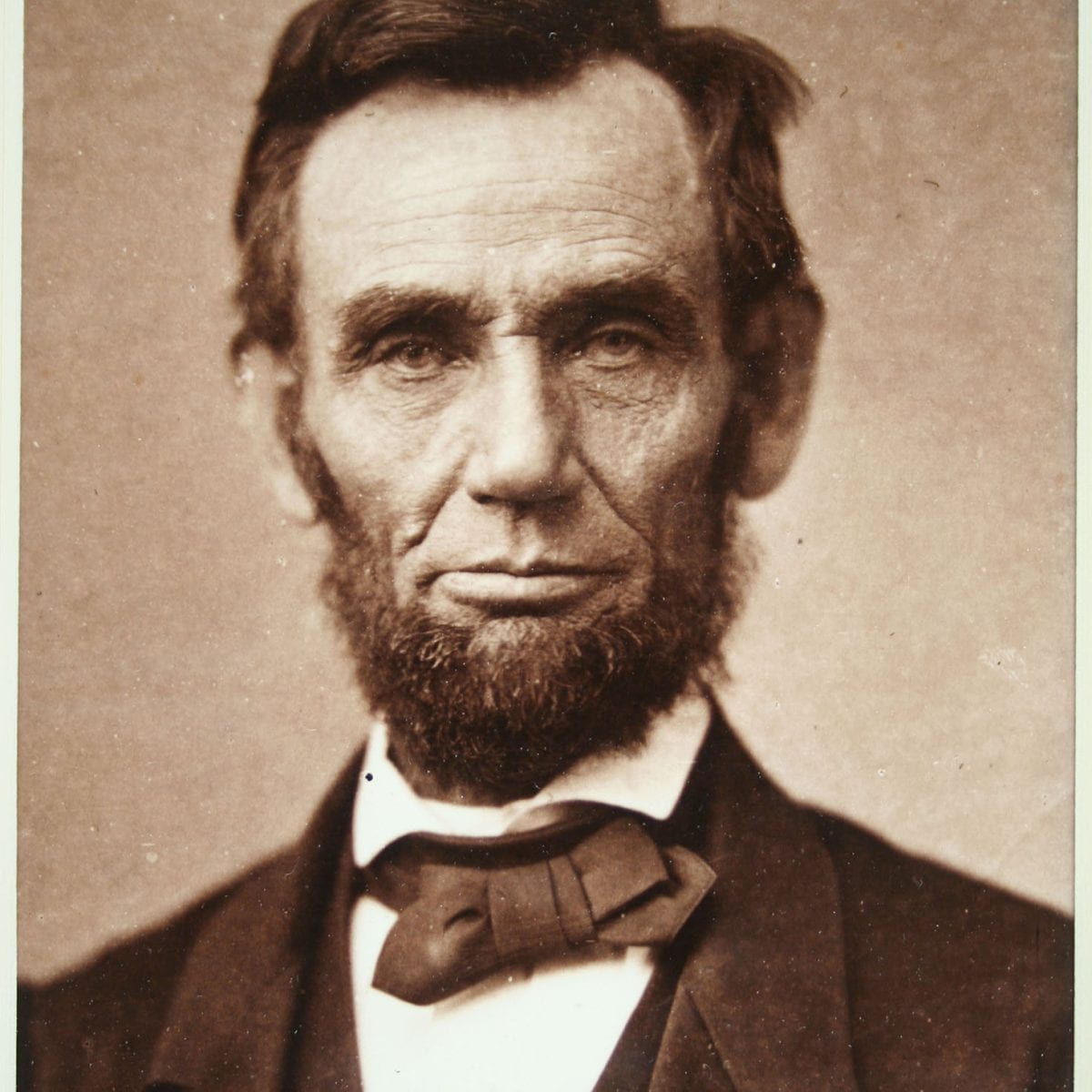

A special post in honor of President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday.

On February 12, we celebrate the birthday of “the People’s President,” Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln is remembered as the savior of the Union, emancipator of enslaved Americans and, sadly, his assassination just 42 days into his second presidential term. Since his untimely death, Lincoln has been celebrated in many different ways. Christians uphold him as a true man of God, commercial companies exploit his image, and the American public sees themselves in a self-made man from the prairie. Both sides of the political aisle claim him as their own. Republicans see an ideal image of Republican elitism that the party has since lost, while Democrats see a man who forged a path for the democratic equality promised in the Constitution. These contradictions are the result of what may be the most interesting part of Lincoln’s legacy: what he might have done if he had survived that fateful night in Ford’s Theatre.

At the time of Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, the United States had just begun the lengthy and painful process of reconstruction. Union soldiers still occupied many of the former Confederate States in an attempt to quell violence. The news of emancipation still had not reached the westernmost states, and would not for another two months. Anger, fear and grief clouded much of the joy felt at the end of a bloody war. Much of the South was struggling to rebuild from the devastation of Sherman’s March. In the midst of the chaos, a broken nation looked to Lincoln to lead them out from the darkness.

Lincoln’s initial plans were announced in the 1863 Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. While not a long-term solution, it was a first bid to return southern states to the Union. The proclamation only required ten percent of a state’s white, male population to swear an oath of allegiance and accept the abolition of slavery. At that time, statehood would be granted and Confederates would be pardoned. It was a generous offer, but one that was harshly rebuked across the South. Despite disagreements, by 1864, Tennessee and the border states including Maryland, West Virginia and Missouri had ended enslavement and rejoined the Union. In 1864 Congress attempted to tighten the requirements for readmission. The proposed Wade-Davis Bill also required the end of slavery but increased the requirement to 50 percent of the white, male population taking an oath of allegiance. Lincoln struck down the bill and instead advocated for forgiveness and speedy recovery.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation was enacted in January 1863, the hard work of enforcing the executive order only began after General Robert E. Lee’s surrender in April 1865. Union forces occupied much of the South, but their presence did nothing to ensure peace in freedom. The Freedmen’s Bureau Acts were an attempt to provide financial and medical support to “displaced southerners,” which included newly free African Americans, but Lincoln died just one month after signing the bill. Without Lincoln as a central guiding figure, Congress struggled to agree on what should be done. President Andrew Johnson repeatedly fought against Republicans in Congress who saw the question as a state issue. As a result, many formerly Confederate states passed legislation to disenfranchise Black citizens, to create separate public spaces for Black and White, and most looked the other way as horrific acts of violence were committed against freed Black families.

“… the disheartening failure of the country to fulfill the promise of emancipation and invoked in his name a renewed struggle for political and civil liberty.”

Lincoln in American Memory, pg 168

By 1908, as tension and violence were continuing to rise, community leaders seeking change called for a “Lincoln Conference on the Negro Question.” Many believed that, had Lincoln lived, he would have prevented much of the violence and the segregation policies. The call for the conference was made on Lincoln’s 100th birthday; it was held the following May in New York. At its conclusion, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was established with the mission of “the completion of the work…the Great Emancipator began.” While this was the popular view of Lincoln, some sought to spin his views with a different interpretation. In the South, the popular idea was that, while Lincoln freed the enslaved, he did not believe that Black and White people could live together in peace. Instead, they felt he would have attempted to send the formerly enslaved to Africa. One congressman even proposed legislation to facilitate the “return” of Black citizens, despite the fact that all but a few were born in the United States.

While Lincoln’s political legacy may forever be debated, there is another interesting facet of his legacy. Beginning almost immediately after the news of his death, people have collected artifacts and memorabilia related to the president. The terms “Lincolnalia” and “Lincolniana” have been used to describe these objects. Collectors seek anything related to Lincoln, such as this scrap of wallpaper from Ford’s Theatre, now held in the Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection (AS 2016.11B, 1865). A cabin Lincoln built in 1830 was displayed around the country, and then disappeared. A man named Osborn H. Oldroyd moved into Lincoln’s Springfield home and turned it into a museum filled with objects such as clothes, portraits, signed letters and sheet music.

Oldroyd convinced Robert Todd Lincoln to donate the house to the State of Illinois for preservation. The collector also eventually acquired the chair Lincoln was sitting in when he was shot, as well as the Lincoln family Bible. His collection was on view in the D.C. home where Lincoln died, and was purchased by Congress for $50,000. Even Lincoln’s contemporaries anticipated what an important figure he would be even a century later, Robert Todd Lincoln was told, “Your father belongs to future ages.” Today, nearly 158 years after Lincoln’s death, there remains a certain obsession with his character and story. The nation still looks to him in times of strife, and hopes that we may be on the path of creating something of which he could be proud.