By Matthew Goetz

Ph.D. Candidate

As a doctoral student in the GW History Department, I love historical trivia. One of my favorite questions is: What is the first monument built in Washington, D.C.? I’m usually met with surprised and confused faces when I give the answer: the Tripoli Monument. Built in 1808 to commemorate the officers in the American navy who perished fighting against Tripoli in the Tripolitan War, or First Barbary War, the Tripoli Monument remained the only monument in the nation’s capital for thirty-five years. It also has the distinction of being the first monument built to honor the American military. Though no longer in Washington, D.C., it still stands to this day on the grounds of the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

The Tripolitan War began in 1801 when the Bashaw [ruler] of Tripoli, one of the “Barbary States” of North Africa (along with Morocco, Algiers, and Tunis) threatened to attack American ships unless the United States government paid him an annual tribute. Since the late Middle Ages, the Barbary States had staged routine attacks on the ships of Christian nations and held their crew for ransom. If, however, a Christian nation paid annual tribute (essentially protection money), the Barbary States would grant their ships safe passage. During the colonial era, Americans were protected from the “Barbary pirates,” as they were then known, by the British navy, but became prime targets when they declared their independence. In response to the threat from Tripoli, President Thomas Jefferson dispatched the American navy to the Mediterranean Sea to protect the nation’s sailors from attack. The Tripolitan War had begun.

Most Americans anticipated an easy victory, but instead the war dragged on for four years and led to the death of several dozen American sailors. By 1805, however, after a naval bombardment of Tripoli city combined with a marine-led invasion across the deserts of North Africa – providing the line “to the shores of Tripoli” to the Marine’s Hymn – the American military successfully forced Tripoli to cease all attacks on American ships. According to historian David Dzurec, the end of the war unleashed “an explosion of nationalism” in the United States as the American people celebrated their victory and honored the soldiers and sailors who made it possible. Some cities celebrated with firework displays while others held public dinners where attendees offered patriotic toasts to “Our gallant Tars [sailors] in the Mediterranean.”

Shortly after the fighting had ended, officers in the American navy decided to construct a monument to honor their fellow officers who had lost their lives in the war. They selected Captain David Porter to organize the operation. To pay for the construction and transportation of the monument, Porter initiated a fundraiser amongst his fellow naval officers. Those who wished to donate could give a set amount of money based on their rank, with captains giving $20 and midshipman $5.

For the design of the monument, Porter considered several proposals, but eventually chose a composition which he claimed to have created himself. The design (and, ultimately, the finished product) included a twenty-three-foot-tall column set on top of a sixteen-foot square base, all carved of “the purest white marble,” in the words of the Alexandria Daily Advertiser. Surrounding the column were several statutes of allegorical figures representing “fame,” “history,” “commerce,” and “America.” The base also contained several inscriptions, including the names of all six American officers who perished in the war: Richard Somers, James Caldwell, James Decatur, John Dorsey, Joseph Israel, and Henry Wadsworth. To sculpt the monument, Porter hired an Italian artist, Giovanni Charles Micali of Livorno, who completed the work within less than a year. Porter then used the naval frigate USS Constitution to transport the monument to the United States in fifty-one separate boxes weighing a total of fifteen tons. Congress agreed to nix the tax usually levied on imports so that it could be brought to the United States free of charge. The monument arrived in North America in the fall of 1807.

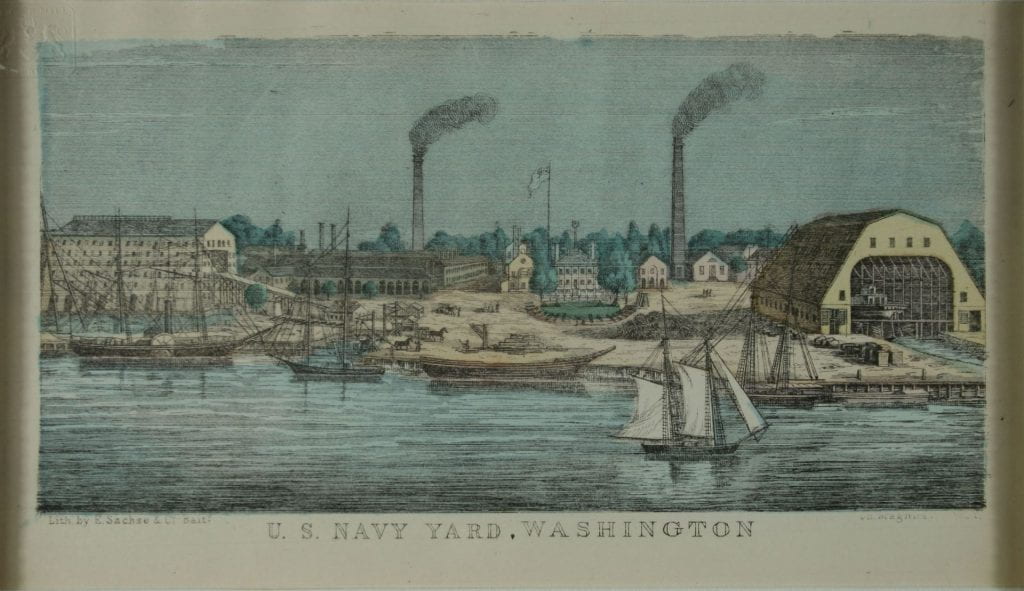

The officers in the navy had always envisioned the young national capital, Washington, D.C., as the logical spot for the monument, but there were disagreements over where in the city to place it. Some suggested the capitol building, but it was still under construction. Instead, the officers chose the entrance to the Navy Yard, the headquarters of the navy during its early years. Benjamin Latrobe, an architect who worked on the construction of the capitol building and the White House, supervised its assembly, and paid for it by auctioning off some of the marble pieces in the foundation that had cracked during its transportation across the Atlantic.

The monument appears to have been quite popular in its early years in D.C., with one newspaper remarking that its “grandeur of design, elegance of execution and size, far excels anything of the kind ever seen on this side of the Atlantic.” According to historian Gene Allen Smith, the Tripoli monument’s placement at the entrance to the Navy Yard “where it could be seen across the city” helped make it “a popular feature in Washington.” The Navy Yard was not only the headquarters of the navy but also a bustling shipbuilding facility, surrounded by a busy commercial district, which provided plenty of foot traffic for viewing the sculpture. But the Tripoli monument appears to have been admired even by those who lived outside of Washington. In 1808, a theater in Providence, Rhode Island, charged attendees 25 cents to view “a grand transparent representation” of it. Despite its relative popularity, the monument did have its share of critics. Art historian Janet Headley notes that its style quickly became outdated in the United States of the early nineteenth century, a nation undergoing rapid cultural change, and that many Americans did not understand the allegorical statues that adorned the sculpture. Still, its antiquated style and enigmatic allegorical themes did not stop a visitor to D.C. in the 1820s from calling it “one of the handsomest and most chaste little monuments I have ever seen.”

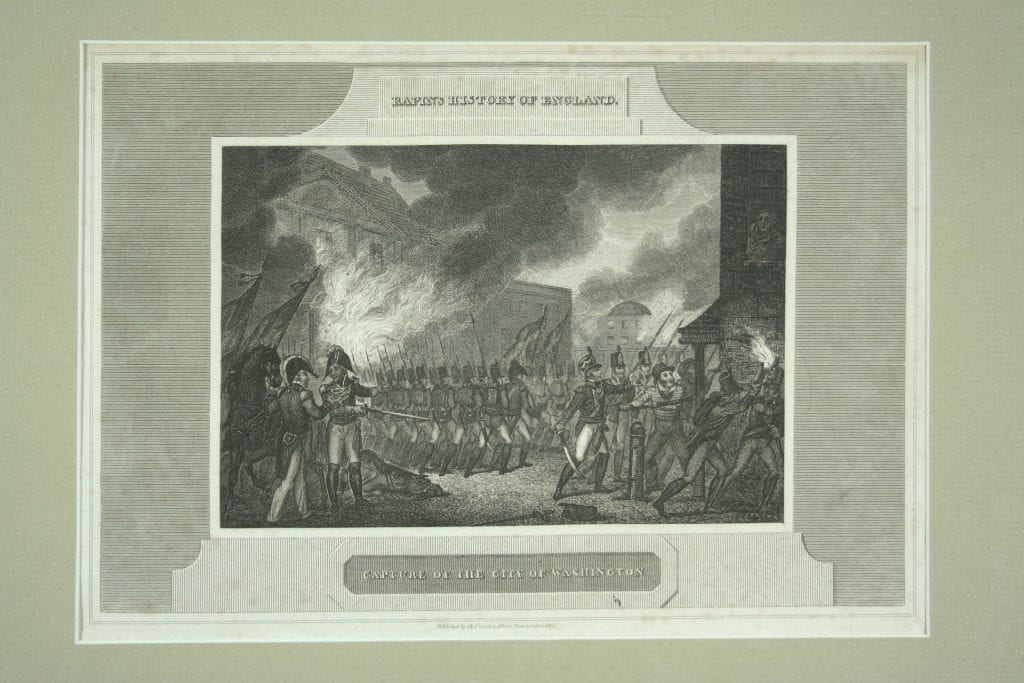

During the War of 1812, British soldiers vandalized the Tripoli Monument when they seized control of Washington, D.C. They broke off several fingers from one of the statues and the entire hand of another, an act the Washington-based National Intelligencer hyperbolically called “the most base and wanton” act of vandalism committed by the British during their invasion of the city (who had also burned the White House and Capitol building). The monument remained broken until 1831, when Congress authorized funds to repair it and move it to a new location on the grounds of the Capitol building. Congress hoped that the Tripoli monument would help embellish the capitol which had recently completed repairs after also suffering damage from British soldiers. In its new location, the monument sat on the western terrace of the capitol grounds facing the national mall, situated inside of a small fountain filled with goldfish – intended to represent the Mediterranean Sea. Captain Porter was disturbed by its new location and placement within the fountain, lamenting the “absurdity” of situating it in “a small circular pond of dirty fresh water.” Porter was not the only critic of the new location. Almost immediately, discussions began over whether to move it again. In 1835, Congress debated placing the monument in the nearby Botanical Gardens, though they ultimately decided against it. In 1860, however, Congress authorized the transfer of the monument to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where it remains to this day.

Despite the monument’s modern-day obscurity, it was relatively popular when first erected. To early Americans, it stood as a symbol of the courage and self-sacrifice of the nation’s military heroes. Now, however, it sits as a mostly forgotten monument to a mostly forgotten war.

Citations

Alexandria Daily Advertiser (Alexandria, VA), November 28, 1807. Early American

Newspapers.

Eastern Argus (Portland, ME), November 8, 1805. Early American Newspapers.

Dzurec, David. Our Suffering Brethren: Foreign Captivity and Nationalism in the Early United

States. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019.

Farmer’s Repository (Charles Town, WV), November 3, 1814. Early American Newspapers.

Headley, Janet. “The Monument without a Public: The Case of the Tripoli Monument.”

Winterthur Portfolio 29:4 (1994): 247-264.

Smith, Gene Allen. “The Tripoli Monument: Commemorating Our Forgotten Past.” Journal of

Maritime Archaeology 15 (2020): 291-305.